Recently more people have been tossing around the idea that an open social network enabler could be the Next Big Thing.

John Battelle wrote that

“PageRank was based on a big graph: the links that make up the web. The next breakthrough, many argue, will be based on the social graph, the links between us all.”

Earlier this spring David Sacks posted on TechCrunch about portals moving “from browse to search to share.”

Little surprise then that one of the more interesting (and well attended) sessions at this weekend’s BarCampBlock was Brad Fitzpatrick (LiveJournal founder who reportedly has joined Google), David Recordon (OpenID, now at 6A), and Joseph Smarr (Plaxo) on the open social graph.

“Social graph,” for the record, is what Facebook calls the map of how their users are connected to each other. Brad has been working on a distributed alternative for a while and he recently jelled his ideas together into a well thought-out essay.

(If you haven’t yet read the piece, you should go read it now).

The problem, in short, is the lack of a way to connect people across services. Anyone who has signed up to more than a single Web service will recognize the issue.

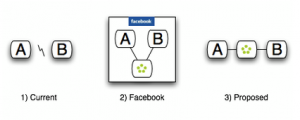

Web services should be able to freely combine. But as it stands each Web service has to implement their own user accounts and friend policy (the social graph). We want simple services that do just one thing really well – for instance, I might use Tripit or Dopplr to share my travel and Goodreads to share my books – but the cost of maintaining accounts on multiple services is too high if they all require me to add and update my contacts manually.

The lack of interoperability between Web apps left open the opportunity for Facebook to create an environment where it’s easy to develop new apps without needing to waste time implementing user accounts and friend policies (Facebook already provides those for you). Users can fluidly discover what apps their friends are on and quickly add new ones without having to create new accounts and add contacts each time. Facebook has critical mass – that is to say, enough people are on it that this actually works.

The problem, however, is that the apps interoperate only within the closed world of Facebook. It would be better to have real interoperability between independent apps.

Brad’s solution is to create a service where people go to aggregate all their networks into a master network, and then let other services check against that to automate friend discovery. The outcome to the user who signs up to a new service should be “These 8 friends of yours are already users here, would you like to share your books / music / pictures / trips / etc. with them?”

Furthermore, the proposal is that the service that hosts the master networks (or administers the code that generates them if people run it on their own servers) should be run by a nonprofit.

This is a familiar scenario: all services benefit from certain shared data, such as track IDs (music), ISBNs (books), and now people. The idea in giving the project to a nonprofit to run is to get competing services on board and ensure impartiality.

People look for two qualities in this type of infrastructure provider: 1) critical mass and 2) ethics. It should appear stable enough that it’s reasonable to expect it to stick around for a while, and since we trust it with our data its intentions have to come across as good not evil.

My initial reaction is it doesn’t matter if the provider is a business or a nonprofit as long as the two criteria are met. The MusicBrainz / CDDB case is illustrative of the difficulties one can run into both when a for-profit service starts misbehaving and when a nonprofit that takes over its job struggles without critical mass. There are positive examples too. Wikipedia is a nonprofit with critical mass; Google is, for most people, still an ethically acceptable ad/map provider.

The discussion‘s ongoing. Some prefer a more radically decentralized approach. Brad’s piece inspired Dave Winer to do a podcast on the topic. His conclusion:

“a network that, from Day One, allows users of other networks to participate, and allows developers to access user’s data, with the user’s permission, but without permission from the network, may become the www of open identity systems.”

See also: An open Facebook?